Tensions in the Caribbean Sea: Analysing the possibilities of a military confrontation between the United States and Venezuela

- alessia988

- Sep 10, 2025

- 11 min read

By Dyami Intelligence Analysis Center

Intel cut-off time: 09/09/2025 17:00 UTC+2

What is happening in the Caribbean?

A land invasion of Venezuela appears improbable given the low number of assets and a lack of military forces in the country’s vicinity, compared to similar actions by the US in Granada (1983) and Panama (1989).

According to available information, there is no indication that eight US warships are deployed in Venezuelan territorial waters or its exclusive economic zone (EEZ). Four vessels, three guided missile destroyers and a cruiser, appeared to be deployed near waters between eastern Venezuela and Trinidad and Tobago. An additional three are part of an amphibious assault group involved in military exercises in Puerto Rico.

On 7–8 September, US Secretary of War Peter Hegseth visited troops in Puerto Rico and aboard the USS Iwo Jima, where he instructed the vessel to be prepared for counter-narcotics operations.

On the night of August 29, 2025 the USS Lake Erie was spotted crossing the Panama canal towards the Caribbean. By August 29, 2025 US officials and media confirmed seven US warships, along with one nuclear powered submarine had either arrived or were on the verge of arriving in the region, not specifying any locations.

On August 19, 2025, the United States stated that it would deploy warships to the Venezuelan coast to conduct an anti-narcotics operation. The specific anti-narcotics mission objectives include drug interdiction operations targeting Latin American drug cartels and affiliated criminal groups.

On 2 September 2025 United States forces struck a speedboat that had departed San Juan de Unare, Venezuela, bound for an unidentified port in Trinidad and Tobago, allegedly transporting narcotics and resulting in 11 reported fatalities. President Donald Trump released video of the incident, describing the occupants as terrorists moving drugs through international waters, while Venezuela’s Communications Minister claimed the footage was fabricated using artificial intelligence. At the time of reporting President Maduro had not issued a statement. Analysis of the imagery raises doubts over the reported casualty figure, as fewer individuals appear on board than the 11 stated officially. The vessel’s size and configuration are consistent with fishing boats commonly used in the Peninsula de Paria, Sucre State, a region long associated with narcotics and human trafficking. According to reports, two drug-laden boats had departed San Juan de Unare shortly before the targeted boat, supporting the likelihood of narcotics trafficking activity. Further credible assessments suggest the strike may have occurred on the Atlantic Ocean side of the area rather than in the Caribbean as initially assumed.

In the early August of 2025, US officials intensified rhetoric against the Venezuelan president, accusing his government of running large scale drug trafficking operations through a network known as the ‘’Cartel de los Soles’’ and designating it as a terrorist organization in July 2025.

President Trump appears to be continuing his first-term approach to Venezuela, maintaining maximum pressure on its leadership through measures linked to organised crime and terrorism; the August 2025 authorisation of military force against drug cartels seems to have been applied for the first time in or near Venezuela’s EEZ. More broadly, US policy towards Venezuela has evolved across administrations, with the country designated a national security concern under Obama and sanctions imposed on senior officials during both the Chávez and Maduro governments.

On Monday September 1, Maduro responded with a rare press conference stating that the United States are seeking a regime change through military threat and that his country is peaceful but will not bow to threats. The Venezuelan President said ‘’Venezuela’s military is super prepared’’ and added that if the U.S. forces attack Venezuela, the country would declare a state of armed resistance and military mobilization.

The possibility of a US military intervention in Venezuela

Despite President Maduro’s claims of a ‘US military threat,’ there is no evidence at present that the United States is preparing for a land invasion of Venezuela. The 1983 invasion of Grenada involved between 6,000 and 7,000 troops on an island of 344 km², while the 1989 operation in Panama required around 26,000 personnel in a country of about 75,000 km². By contrast, the stretch of coastline in Venezuela 100 km deep is about 65,000 km², while the country itself covers 915,000 km². A military invasion into Venezuela would require more than double the assets currently deployed in the southern Caribbean, along with an increase in troop numbers and hardware from US military bases in neighbouring countries. Such an effort would necessitate a surge in military transport flights, something not observed in open sources.

Additionally, major powers such as China, Russia and Iran are expected to act as a deterrence against either a change in government in Venezuela or direct military intervention by the US. At different moments over the past two decades, these countries have invested in Venezuela’s security and energy sector:

China channelled roughly €52–55 billion to Venezuela in 2007–2016 through oil-backed loans and joint funds focused on energy and infrastructure and in May 2024 both sides signed a bilateral investment-protection treaty that underpins future projects.

Russia supplied around $9 billion in arms by 2013 and invested roughly $8 billion in Venezuelan oil ventures that were later moved from Rosneft to the state company Roszarubezhneft. In July 2025 Rostec opened an ammunition plant in Maracay aimed at producing up to 70 million 7.62×39 cartridges a year.

Iran has concentrated on the energy sector with a €110 million contract to repair the El Palito refinery plus a €460 million revamp agreement for the Paraguaná complex alongside a 20-year cooperation roadmap and defence-industrial ties such as assembly of Arpía/Mohajer-2 UAV, preceded by a €23 million contract for Iranian Mohajer-2 UAVs and an overall UAV programme for reconnaissance and loitering munition drones.

Given these countries’ involvement and investments in Venezuela they are expected to provide political and security support as a means of deterrence against any possible US intervention. The extent of their involvement in military terms should a US intervention take place remains undetermined, particularly should the US only carry out aerial strikes on Venezuela.

Given the information available, a US land invasion into Venezuela is not probable at the time of writing. Energy security, however, appears to be a major factor in the continued pressure, as Venezuelan heavy crude remains well suited for US Gulf Coast refineries despite the shift in export flows towards China.

Reports of US warships deployed in the Caribbean sea near Venezuela

The breakdown of United States military deployments in the southern Caribbean shows guided missile destroyers USS Gravely, USS Jason Dunham and USS Sampson, as well as the guided missile cruiser USS Lake Erie, operating somewhere in the region of Venezuela’s exclusive economic zone. Their location is more likely than not off the eastern Venezuelan coast near Trinidad and Tobago, based on the inference that a Hellfire missile was used against a motor boat on 2 September. This missile is deployed from an SH-60 Seahawk helicopter and has an operational range of approximately 350 kilometres, thereby situating the probable launch zone within that radius. It is anticipated that additional United States aircraft may be deployed to Curaçao in support of this mission, in which event Venezuela is expected to heighten its surveillance of the islands. Venezuelan spotters are known to operate there, monitoring the United States Forward Operating Location (FOL) and other sites, reporting every inbound and outbound movement directly to Caracas. Activity on the islands cannot be concealed and this has long constituted the established modus operandi, employing a variety of tactics and manoeuvres designed to obscure operations.

At the same time there are strong indications that three navy vessels, the transport dock ships USS San Antonio and USS Fort Lauderdale and the assault ship USS Iwo Jima, that were off the coast of Guayana, Puerto Rico may now be deployed either near Trinidad and Tobago, or Guyana. These were taking part in amphibious landing exercises which began on 31 August involving around 4,500 troops of the 22nd Marine Expeditionary Unit. The Iwo Jima, essentially a small aircraft carrier, carries Osprey, Chinook, Huey, Blackhawk and Cobra helicopters as well as vertical take off aircraft such as the Harrier and possibly F-35s. Although the F-35 is capable of both intelligence-gathering and combat tasks, the USS Iwo Jima does not yet appear cleared to operate the aircraft. For the exercise in Puerto Rico, a more plausible configuration involves AV-8B Harrier IIs in multi-role capacity, MV-22 Ospreys, AH-1Z Vipers, CH-53E Super Stallions and UH-1Y Venoms, covering both light and heavy lift requirements. The subsequent deployment between Trinidad and Tobago and Guyana appears intended as a deterrent with movements not directly indicative of operations against Venezuela, while the location of the transport dock ships remains unknown. However, the troop levels involved fall short of what would be required for any credible deployment scenario in Venezuela.

Military flights in the region also point to a connection with the ongoing military drills in Puerto Rico. A P-8 Poseidon reconnaissance aircraft has also been observed flying between Puerto Rico and Florida, but not southward towards Venezuelan waters. A series of military flights involving mainly C-17 Globemaster and C-130 Hercules transport aircraft were tracked between 27 August and 2 September, all flying between Puerto Rico and the United States, Trinidad and Tobago or the neighbouring US Virgin Islands. This initially suggested that flights in the region were focused on supplies to Puerto Rico and the ongoing military drills, but now point to a deployment beyond the US island territory in light of official footage of Harrier aircraft flying above Georgetown, Guyana between 7 and 8 September during the country’s presidential inauguration.

An amphibious ready group is normally made up of an amphibious assault vessel, a dock landing ship, amphibious transport docks and a contingent of marines. The Puerto Rico deployment features two transport dock vessels but no dock landing ship, diverging from the standard structure of such a group. This makes it more likely that the presence of USS San Antonio, USS Fort Lauderdale, USS Iwo Jima and the Marine Expeditionary Unit represents a demonstration of force rather than a direct preparation for operations inside Venezuela.

Trump’s policies towards Venezuela

Recent developments suggest a shift in United States policy under President Trump towards Venezuela, with greater emphasis on security and organised crime. In March, the White House stated that President Maduro had facilitated the infiltration of the Tren de Aragua group, designated by Washington as a Foreign Terrorist Organisation, into the United States. The statement also linked Venezuela’s internal conditions to wider regional pressures through migration and instability. In July, the US Treasury sanctioned the Cartel de los Soles, alleging involvement by senior Venezuelan figures in narcotics trafficking. Together these actions reflect a hardening of tone, portraying Venezuela not only in terms of governance concerns but also in connection with transnational criminal activity.

In August, this approach was reinforced through a broader directive. On 7 August, President Trump signed an order authorising US military action against drug-smuggling cartels and criminal groups if national security was considered at risk, a step initially met with concern in Mexico. While the directive was not specific to Venezuela, it provides Washington with greater latitude to apply pressure in the region. The combination of sanctions, accusations of organised crime and the authorisation of military measures points to an evolving US policy that increasingly links Venezuelan actors to hemispheric security challenges.

Energy security: Venezuela’s shift to China instead of the US, US presence in Guyana

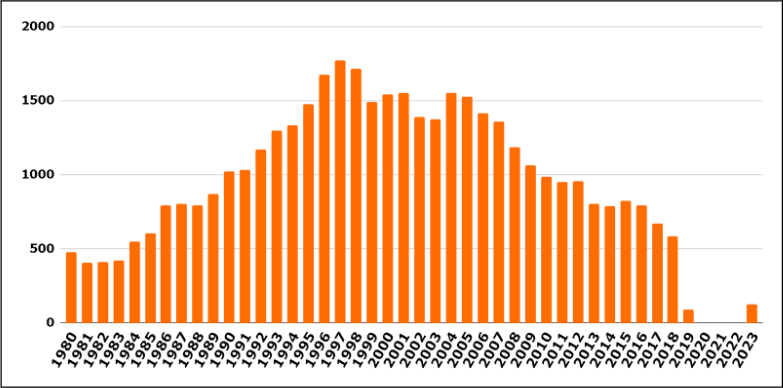

Venezuela’s trade relationships have shifted significantly, particularly with the United States. Although the share of Venezuelan crude sent to US refineries has declined, the country’s heavy crude oil remains well suited for Gulf Coast facilities. In 2019, about 41% of Venezuela’s crude exports went to the United States but by 2023 this had dropped to 23% while China’s share rose from 25% to 69%. Over this six year period exports to the United States were cut in half while exports to China almost tripled, underlining the impact of sanctions and the central role of economic considerations in US policy. Even with the US administration’s decision in July 2025 to renew Chevron’s licence for limited operations in Venezuela, American investment and activity in the country remain restricted.

US crude oil imports from Venezuela between 1980 and 2023

Source: US Energy Information Administration

US energy investment in Venezuela has largely dried up while capital has flowed into neighbouring Guyana. After major offshore hydrocarbon discoveries in 2015, Guyana began producing oil in 2019 and has since become central to US energy security, with US firms investing about €12.3 billion, roughly 96% of the country’s total foreign direct investment between 2020 and 2024. In parallel Washington is strengthening its military posture in the Caribbean; at Guyana’s presidential inauguration on 8 September the US Embassy in Georgetown reaffirmed support for the country’s defence, signalling a remit that extends beyond counter-narcotics to protecting Guyana as it contests a decades-long territorial dispute with Venezuela that includes offshore reserves.

Official notification from the US Embassy in Guyana on support for the country’s territorial integrity amid an ongoing territorial dispute with Venezuela

In the longer term, the steady increase of Venezuelan crude exports to China, driven by rising energy demand, could solidify a durable partnership between both countries. This would come at Washington’s expense, as it risks not only losing access to a decades-long supplier but also seeing an increasing presence of China in areas perceived as its traditional zone of influence. From a strategic perspective, the United States has an interest in keeping Venezuela within its energy orbit, as well as reducing the growing Chinese influence in its side of the hemisphere. Venezuela’s reserves of hydrocarbons, discovered to be the largest in the world in the late 2000s, are an essential strategic interest that the current US leadership appears very focused on pursuing, in addition to Guyana’s, determined to be one of the largest reserves in the world found since 2015.

Following this logic, in March 2025, US President Trump signed an Executive Order imposing 25% tariffs on all goods from countries that import oil from Venezuela. Both Trump administrations issued rewards for information leading to the arrest or conviction of Venezuelan leader Nicolas Maduro, officially offering a $15 million reward in 2020, increased to $25 million in January 2025, and $50 million in August of the same year. The deployment of military assets in the region and narcotics trafficking charges against Venezuela’s leadership, combined with unilateral strikes on vessels departing or near its exclusive economic zone, serve as instruments of pressure designed to push Caracas towards a negotiated arrangement by President Trump as “making a deal,” bringing its government policies more in line with US interests.

Official bounty increases issued by the US Government against of Nicolas Maduro in January (below left) and August (below right) 2025

Looking ahead

The prospect of a United States military intervention in Venezuela remains limited at present. Force levels in the southern Caribbean including guided missile destroyers, an amphibious group exercising in Puerto Rico or a deployment of the USS Iwo Jima near Guyana or Trinidad and Tobago do not match what would be required for a land operation. Historical precedents in Grenada and Panama point to far larger commitments than are currently visible. Any campaign against Venezuela would require a much greater build up of personnel logistics and transport capacity, none of which appears in open source reporting. Instead Washington is pursuing a calibrated strategy of coercion short of invasion that uses sanctions, legal designations, tying Venezuelan actors to narcotics trafficking and terrorism, and selective strikes such as the 2 September action against a Venezuelan vessel. This approach signals capability and intent while avoiding the burdens of a protracted conflict.

The current US force posture in the Caribbean does not indicate preparations for a land invasion of Venezuela or a large-scale, sustained air campaign. The composition and size of deployed assets appear disproportionate to counter-narcotics missions and insufficient for a rapid invasion scenario akin to Panama in 1989, suggesting the posture is intended primarily as strategic pressure. A limited, high-risk contingency such as a targeted raid against Venezuelan leadership cannot be ruled out, though it would require extensive diversionary and electronic warfare measures beyond a special task group.

Regional dynamics further reduce the likelihood of direct intervention. China is Venezuela’s dominant buyer of crude and Russia provides diplomatic and limited military technical support, which raises the cost of escalation for Washington. Sustained US naval and air activity and the absence of Venezuelan deescalation measures keep uncertainty high. A video that purported to show Venezuelan F-16s over a US warship has been assessed as misleading by some experts, with the ship identified as Venezuela’s own Guaiqueri class patrol vessel. A direct engagement by Caracas with US naval assets would be a serious escalation. The exact disposition of US destroyers whether inside Venezuela’s EEZ or just outside near Trinidad and Tobago remains unclear, but it is unlikely that President Maduro would court confrontation given Venezuela’s limited capacity to withstand escalation against superior US forces.

Regional stability and civilian sectors are also at stake. Ongoing operations and the prospect of further incidents may depress European and US travel to the ABC islands of Aruba Bonaire and Curaçao. Dutch defence and state ministers have advised parliament that commercial flight risk has not increased and that authorities are monitoring developments while treating the activity as a US national operation. Taken together the indicators point to sustained pressure rather than invasion with sanctions, military signalling, and reputational tools used to constrain Caracas and shape its behaviour short of a direct campaign.